Without the sinking, the fame of Titanic is greatly diminished. It would be merely a footnote in the engineering history of the early twentieth century.

The sinking of the “unsinkable” ship leading to an “unthinkable” fate for those aboard caused by an “unimaginable” bad fortune and bad management is the reason we are still captivated by this tale a century later.

In this section, we will be explaining in simple terms how? Why? When? and where? Titanic sank.

A Complete Titanic TEACHING UNIT

A complete unit of work to teach students about the historical and cultural impact Titanic made upon the world both back in the early 20th century. This complete unit includes.

How did the Titanic Sink?

There were many elements contributing to the sinking of Titanic, but the striking of an Iceberg rupturing her steel hull on April 14th 1912 was the fatal blow that crippled the ship and caused it to sink just over two hours later. Read on to explore the events of this evening in far greater detail.

“Deeply regret to advise you TITANIC sank this morning after collision with an iceberg, resulting in a serious loss of life. Full particulars later.”

J. Bruce Ismay, Director of the White Star Line upon his return to New York.

WHEN DID TITANIC SINK?

The Titanic sunk on Monday, April 15, 1912, at 2:20 am. Only two hours and forty minutes after she struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean. The iceberg collision ripped open Titanic’s hull in several places, including her five watertight compartments. The rate at which Titanic sank was quite rapid for a ship of such size.

Titanic carried 2224 people of all age, gender and social class that fateful night and only 710 escaped in lifeboats who the RMS Carpathia later rescued. 1514 people died in the icy waters. The dead mainly consisted of men who offered their limited lifeboat spaces to the many women children on board. The bulk of those men who perished primarily came from the ship’s second class passengers with ninety percent of these men perishing in the icy waters.

Although this was a completely avoidable and unnecessary tragedy, the Titanic disaster brought about widespread innovation and regulation in ship-building, materials manufacturing, and sailing vessel standards and practices on both sides of the Atlantic to ensure a disaster of this scale could not be replicated.

It has also been speculated that all forms of trade were profoundly affected by the tragedy’s ramifications. The Titanic gave us a grim picture of the reality of maritime disasters at the very birth of the international travel industry.

The sinking of the titanic was a mixture of bad luck and terrible management. This page outlines the timeline of events that led to the Titanic’s sinking on April 14, 1912.

RMS TITANIC SINKING JOURNAL: THE FINAL HOURS OF TITANIC

Sunday, April 14: Afternoon to Evening

The conditions in which Titanic sailed towards New York were almost too good to be true. She was making good time in perfect conditions. Second Officer Charles Lightoller would later state “the sea was like glass.”

Most passengers and crew enjoyed Sunday Luncheon except for the Titanic’s two wireless operators Jack Phillips and his assistant Harold Bride. They were capitalizing on the many personal telegraphs being sent from Titanic’s well-heeled passengers about the grand time they were having onboard the world’s largest ocean liner.

Titanic boasted the most powerful radio telegraph system of any ship in the world in 1912, and it was put to great use by Bride and Philips during Titanic’s maiden voyage. This was even more, so the case on Sunday afternoon as a backlog of telegraphs existed from the previous evening. The radio was out of action for several hours due to a malfunction that was fixed around 5:00 am Sunday morning.

The weight of telegraphs going out from Titanic seemed to dominate the six messages received from nearby ships about iceberg sightings in the area. They did not seem of major concern to many, including Captain Smith, who shared this information with the ship’s owner Bruce Ismay and posted one on the bridge for the crew to see.

Both Ismay and Smith decided that the ship should not be slowed in such optimal conditions; however, Captain Smith ordered the boat to head some ten miles south from its direct line and this should bring her into warmer and safer waters.

At 6:00 p.m. that evening, Second Officer James Lightoller took control of Titanic until 10:00 p.m. During this time, many passengers refused to brave the icy and cold conditions on board the Titanic deck in which she now found herself.

At 7:15 that evening Harold Bride decided to give the stressed wireless radio system a well-deserved break and cool down to take stock of the many inbound messages for passengers.

“The sea was like glass”

Second officer Charles Lightoller

Captain Smith dined with some of the more prestigious passengers under a moonless yet starry sky whilst Lightoller was at the helm.

By 8:55 pm Captain Smith had returned to the bridge in which he and Lightoller had a discussion about the weather conditions. “Yes, it is very cold, sir” Lightoller agreed. “In fact, it is only one degree above freezing. I have sent word down to the carpenter and rung up the engine room and told them it will be freezing during the night.” Charles Lightoller

Captain Smith had decided to retire for the evening but did remind Lightoller to slow the ship if conditions became hazy and inform the crow’s nest on the lookout for bergs.

By 9:30 p.m. the radio room had contacted mainland America and had a mass of telegraphs to communicate to the United States. At this point, Bride made a fateful decision not to pass on an ice warning from the nearby steamer Mesaba warning the titanic of pack ice and large bergs.

Telegraph operator Jack Phillips had now taken over from Harold Bride felt too busy with unsent messages and confident that he had previously sent all other ice-warnings to the bridge as a precaution.

At 10:00 pm, the lights in the public rooms of the second and third class were put out to encourage passengers to head to bed whilst the drinks, cigars, and conversations continued in first class.

Lightoller handed over the helm of Titanic to First officer Murdoch. The pair discussed the conditions and the wishes of Captain Smith if visibility changed. Lightoller went to bed following a quick inspection of the decks.

Jack Phillips was still working furiously in the telegraph room when at around 10:40 pm he received a very loud message from the liner Californian. “Say, Old man, we are stopped and surrounded by ice.” The stressed and tired Phillips replied “Shut up! Shut Up! I am busy.

With no moon or waves and to assist the lookout in detecting icebergs that were already without binoculars, in hindsight it seemed beyond belief that Titanic would steam full-powered to into a well-warned area of icebergs and pack ice.

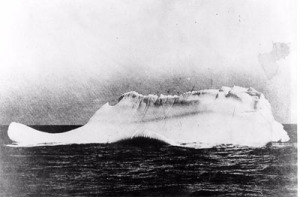

This berg is believed to be the one that Sank Titanic as it had some red paint marks across it and was in the location of Titanic’s distress calls.

Titanic Strikes an ICEBERG

11:40 Pm “Iceberg right ahead.”

were the fateful words that would signal the demise of the grandest ship ever built.

Frederick Fleet was the lookout who raised the alarm first verbally, then immediately sounded the ship’s bell three times and telephoned the bridge to warn them of what they now already could see themselves.

Over 48,000 tonnes of steel ploughed towards a rogue iceberg which was more than likely at least ten times the mass of Titanic.

Approximately 37 seconds later the berg would penetrate Titanic’s Hull. And the decision of what occurred next time fell upon First Officer William Murdoch. The accounts of exactly what happened are both varied and still debated to this day.

The most commonly accepted story is that Murdoch ordered: “Hard a Starboard” driving Titanic’s rudder hard right and hence fully exposed her starboard bow to absorb the blow of the iceberg.

Did speed play a factor in the Sinking of Titanic?

As Titanic embraced the sharp, strong, and jagged crust of the berg, immediate thoughts from the lookout and bridge were that the situation might have been worse had the ship hit directly. And that may be the ‘unsinkable’ ship might live up to her title. Those who lived to tell the story would recall the impact as a mild unexpected vibration of no major significance at the time.

“Just before going to my state room, A11, there was a bump. As I turned the handle of my room [door] there was another bump. As I got into my room, there was a third bump. One of these bumps… like little pushes, nothing violent. I slipped on a coat over my white satin evening dress, and went right out from my own state room because my state room had a door leading to the promenade deck. As I got out onto the promenade deck, I saw a large grey, what looked to me like a building, floating by. But that “building” kept bumping along the rail, and as it bumped it sliced off bits of ice [which] fell all over the deck. We just picked up the ice and started playing snow balls. We thought it was fun. We asked the officers if there was any danger, and they said, “Oh, no, nothing at all, nothing at all, nothing at all. Just a mere nothing. We just hit an iceberg.”

First Class Passenger Edith Louise Rosenbaum Russell, would later recount the immediate aftermath of the collision

The mass of water pouring into Titanic’s lower decks immediately after the impact would tell a very different story which would be confirmed by the ship’s carpenter J. Hutchinson and Titanic’s designer Thomas Andrews.

The collision had forced the metal to buckle inwards and popped rivets below the waterline, opening the first five compartments (the forward peak tank, the three forward holds, and Boiler Room 6) to the sea.

As the forward compartments filled, the watertight doors closed. Any sailors still in these compartments drowned quickly. Titanic could stay afloat with the first four compartments flooded, but it had already taken on water in five compartments, and a sixth was beginning to flood. Captain Smith, alerted by the jolt of the impact, ordered “all-stop” once he arrived on the bridge.

The death of a Titan.

It became very apparent that the Titanic would sink. Thomas Andrews estimated the ship had an hour to an hour and a half and believed that the pumps would only keep Titanic afloat for a few extra minutes at best. The pumps could only cope with 2,000 tons of water per hour, but that quantity was flooding into Titanic every five minutes.

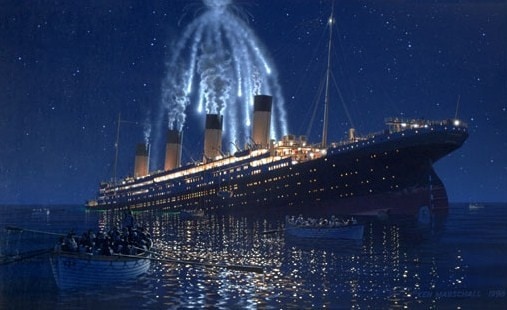

“Women and children first!” – The Deployment of the lifeboats.

At 12:05 – 25 minutes after the collision, Captain Smith ordered that lifeboats be deployed some twenty minutes after that he decreed that women and children shall take precedence. The first lifeboat was actually lowered until 12:45 a.m.

Many passengers had not immediately sought lifeboats as a means of survival on the ‘unsinkable’ Titanic. The boat decks had become an incredibly noisy and unwelcome area of Titanic as she began to founder.

The reason for this was due to the enormous build-up of steam in the ship’s boilers that had to be released from her whistles and funnels located on the lifeboat decks. Less than an hour ago, Titanic’s boilers were running nearly full capacity and were now completely stopped. This steam had to be released to avoid an explosion in the boiler rooms.

Lifeboat #7 was lowered first, on the starboard side, with a mere 28 people on board (26 of who were first-class passengers) on a boat with a maximum capacity of 65. Titanic was built to hold 32 lifeboats but carried only 20: Their total capacity was 1,178, only 53 % of the ship’s total complement of passengers and crew of 2,222.

This paltry number of boats was still more boats than required by the board of trade. The organization that oversaw maritime safety in 1912. At this time, the number of lifeboats required was determined by a ship’s gross tonnage rather than its human capacity. The regulations concerning lifeboat capacity had last been updated in 1894, when the largest ships afloat weighed approximately 10,000 tons, while the Titanic had 46,328.

One positive aspect of the Titanic’s sinking would be the complete overhaul of maritime safety laws around the world for the betterment of the industry.

First and second-class passengers had easy access to the lifeboats with staircases that led right up to the boat deck, but third-class passengers found it much harder. Many found the corridors leading from the lower sections of the ship difficult to navigate and had trouble making their way up to the lifeboats. Some gates separating the third-class section of the ship from the other areas, like the one leading from the aft well deck to the second-class section, are known to have been locked.

While most first and second-class women and children survived the sinking, more third-class women and children were lost than saved. The locked third-class gates were the result of miscommunication between the boat deck and F-G decks. Lifeboats were supposed to be lowered with women and children from the boat deck and then subsequently to pick up F-G Deck women and children from open gangways. Unfortunately, with no boat drill or training for the seamen, the boats were simply lowered into the water without stopping. As a result of the segregation of third class, only one of the 29 children travelling in first and second-class (Lorraine Allison, a two-year-old Canadian girl) perished in the disaster, compared to 53 of the 76 travellings in third.

By 1:25 a. the situation on the lifeboat decks had become chaotic. By now most passengers had concluded there were far more people on Titanic than a position on lifeboats.

The boarding of lifeboats had become increasingly rushed and disorganized as lifeboats were now entering the water overloaded and in a very rushed manner.

As this was Titanic’s maiden voyage, the crew had little understanding or training on expelling her lifeboats and were increasingly losing control of the situation at hand. When Lifeboat #14 was lowered on the port side, with Fifth Officer Harold Lowe in charge. He was forced to fire three shots from his gun into the air along the side of the ship to deter passengers on the boat deck from jumping in as they descended into the water.

In another instance, lifeboat number 11 was nearly lowered directly into the path of one of Titanic’s pumps. Had it not been for some quick thinking of those on board which used the oar to prod the boat away from the pump, there may have been a further 70 fatalities added to Titanic’s lengthy toll.

By 01:35, as Lifeboats #15 and #16 abandoned the ship, all of the boats in the second-class portion of the boat deck were gone. Six lifeboats remained on the ship, all in first-class, with a combined capacity of 293 for the estimated 1,800 people who remained on the ship. Lifeboats collapsible C and D were the last ones to leave the ship.

A major turning point came at 01:40 when the holes for the bow anchors dipped underwater. This allowed the frigid water to flood the rest of the bow until that time dry. Shortly afterwards the ship’s bow suddenly lurched several feet downwards. This was most likely caused by the collapse of the watertight bulkhead between boiler rooms 6 and 5, which a smouldering coal bunker fire had weakened during the voyage. The sudden movement was noticeable to those on board, and the increased angle of tilt further alerted them to the impending danger, leading to outbreaks of panic.

Collapsible C left around 02:00, Collapsible D five minutes later. These boats were the closest to the ship as it foundered. Lifeboat #4 (the boat launched before Collapsible C) picked up those who were caught in the freezing ocean

The Titanic reported its position as 41°46′N 50°14′W. The wreck was found at 41°44′N 49°57′W.

WHERE DID TITANIC SINK?

Wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride were busy sending out distress signals. The message was initially “CQD-MGY, sinking, need immediate assistance,” later interspersed with the newer “SOS” at the suggestion of Bride (CQD was still a widely understood distress signal at the time, and MGY was the Titanic’s call sign). Several ships responded, including the Mount Temple, Frankfurt, and the Titanic’s sister ship, Olympic, but none were close enough to make it in time. The Olympic was over 500 nautical miles (930 km) away. The closest ship to respond was the Cunard Line’s RMS Carpathia, and at 58 nautical miles (107 km) away it would arrive in about four hours, still too late to get to the Titanic in time. Two land-based locations received the Titanic distress call: the wireless station at Cape Race, Newfoundland, and a Marconi telegraph station on top of the Wanamaker’s department store in New York City. Shortly after the distress signal was sent, a radio drama ensued as the signals were transmitted from ship to ship, through Halifax to New York, throughout the country. People began to show up at White Star Line offices in New York almost immediately.

02:00 – Waterline reaches forward boat deck

At first, passengers were reluctant to leave the warm, well-lit, and ostensibly safe Titanic, which showed no outward signs of being in imminent danger, and board small, unlit, open lifeboats. This was one reason most of the boats were launched partially empty: it was perhaps hoped that many people would jump into the water and swim to the boats. Also important was an uncertainty regarding the boats’ structural integrity; it was also feared that the boats might collapse if they were fully loaded before being set in the water, despite being tested with a weight of 70 men.[citation needed] Captain Smith ordered the lifeboats be lowered half-empty in the hope the boats would come back to save people in the water, and some boats were given orders to do just that. Boat #1, meant to hold 40 people, left the Titanic with only 12 people on board. It was rumoured that Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff Gordon bribed the two able seamen and five firefighters to take them and their three companions off the ship. This rumour was later proven false. J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, left on Lifeboat Collapsible C and was criticized by both the American and British Inquiries for not going down with the ship. Other passengers, including Father Thomas Byles and Margaret Brown, helped the women and children into lifeboats.[18][19] Brown was finally forced into a boat, and she survived. Byles did not.

As the ship’s tilt became more apparent, people became nervous, and some lifeboats began leaving with more passengers. “Women and children first” remained the imperative (see the origin of phrase) for loading the boats. The order “women and children first” was given by Captain Smith. It was intended that women and children would be loaded into lifeboats first, and any remaining positions, if available, be allocated to men. In certain circumstances, particularly in the lifeboats overseen by Second Officer Lightoller, this order was translated as women and children only. It should also be noted that over half of the third-class women perished, even though nearly all of the women in first and second class survived.

At 02:05, the waterline reached the bottom of the bridge rail. All the lifeboats, save for the awkwardly located Collapsible A and B, had been lowered. With 3 seats to spare, Collapsible B was the last lifeboat to be lowered from the davits. The total number of vacancies was 466.

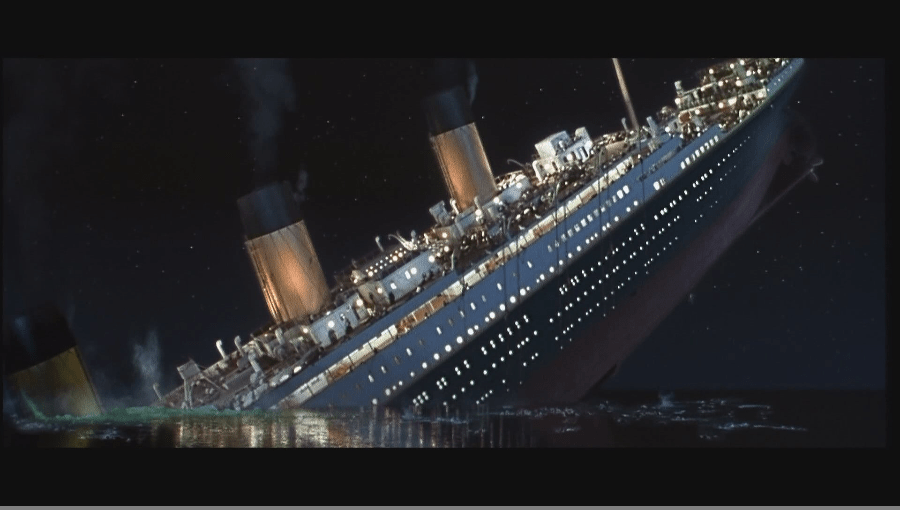

02:05 – Propellers exposed

The sheer volume of water in Titanic’s bow would drag her propellers upwards. Passengers either scampered to higher ground or took a leap of faith into the water around one degree above freezing as lifeboats’ positions became increasingly scarce.

At this point, Titanic’s bronze propellers began to rise above the water line in front of Lifeboat #2, which was just off the stern. Water was beginning to flood the forward boat deck by entering through the crew hatches on the bridge. At this time, Captain Smith released wireless operators Harold Bride and Jack Phillips from their duties; Smith then quietly wandered off into the bridge, making no attempt to save himself. Bride went to their adjoining quarters to gather up their spare money, as Phillips continued working. When Bride returned, he found a fireman unfastening Phillips’ life belt, attempting to steal it without Phillips noticing him. Bride grabbed the fireman, and then the three of them wrestled around in the small room for a few seconds. At one point, Bride grabbed the man by the waist, while Phillips punched him until he finally fell to the floor unconscious. Seeing water now entering the room, Phillips and Bride grabbed their caps and dashed out on the deck, where Bride helped with Collapsible B, and Phillips ran aft.

The lifeboats feared being sucked under when the Titanic sunk like a vacuum and was under instruction to move well away from it until it sunk. Only one boat would return afterwards to an eery silence.

The last two lifeboats floated right off the deck as the icy Atlantic reached them: Collapsible A half-filled with water and Collapsible B upside down with at least 30 men clinging to it. Shortly afterwards the forward expansion joint, located aft of the first funnel, was pulled apart by the rising stern’s weight. This placed an unbearable strain on two of the funnel’s cable stays which were anchored to the boat deck aft of the joint. The cables snapped, and the funnel fell forward, crushing part of the starboard bridge wing. On deck, people scrambled towards the stern or jumped overboard in hopes of reaching a lifeboat.

With the order for women and children first into the lifeboats, plus the knowledge that there were not enough lifeboats for everyone on board the Titanic to be saved, it is a bit surprising that two dogs made it into the lifeboats. Of the nine dogs on board the Titanic, the rescued two were a Pomeranian and a Pekinese.

Father Byles spent his final moments alive reciting the rosary and other prayers, hearing confessions, and giving absolutions to the dozens of people who huddled around him.[21] The ship’s stern rose to about 15 to 35 degrees, until 02:18 when the electrical system failed and the lights, which had burned brightly throughout the whole time, went out permanently. The Titanic’s second funnel then broke off and fell into the water. (Although the second funnel has often been presumed and depicted as staying on the ship until it goes underwater, this would be impossible because none of the funnels would have been able to stand the pressure the water had on the ship. About a quarter of the second funnel was underwater with the other three quarters above the surface at the breaking point. The first funnel was in the same position at the time of its detaching.)

02:20 – Titanic’s final plunge

“And it wasn’t until we were in the lifeboat and rowing away, it wasn’t until then I realized that ship’s going to sink. It hits me there.”

Eva Hart, Titanic Survivor

At approximately 02:18, a few seconds after all electrical power failed on the ship, the superstructure underneath the third funnel completely split, splitting Titanic in half and crushing hundreds of people. The split was between the third and fourth funnels near the aft expansion joint, and the bow section went completely under. The third funnel collapsed shortly after the breakup as the bow sank, and the fourth funnel fell soon after as the stern sank. The stern section was pulled up again by the sinking bow and heavy engines. The stern reached a high angle and surfaced from the water. The stern was reported to have tipped far on its port side as it began to sink, even turning around on the spot. Some reported cries from lifeboats that the ship had returned (shouting, “Look! The men are saved!”). However, after a few moments, the stern section also slid under the North Atlantic’s icy waters, two hours and 40 minutes after the collision with the iceberg.

The White Star Line attempted to persuade surviving crewmen not to state that the hull broke in half, believing that this information would cast doubts upon the company’s vessels’ integrity. However, many believe the stresses inflicted on the hull when it was at 12 degrees to the sea line (bow down and stern in the air) were beyond the structure’s design limits, and 45 degrees proved to be the breaking point. No legitimate engineer could have fairly criticized the work of the shipbuilders in that regard.

The bow and stern took only a few minutes to fall 3,795 meters (12,451 ft.) to land about 600 meters (2,000 ft.) apart on a gently undulating area of the seabed. The streamlined bow section struck the seabed at a speed of about 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) – 30 miles per hour (48 km/h). It skidded along the bottom and gouged out a trench before coming to a halt abruptly, causing the bow to jack-knife and the decks at the rear end to collapse one atop another. Nonetheless, it remained relatively intact. The stern, by contrast, suffered catastrophic damage as it descended. The hull disintegrated as air escaped and bulkheads imploded. When the stern hit the seabed, the decks collapsed on top of each other, causing the remainder of the hull to burst outwards, littering the seabed with huge slabs of crumpled steel. For several more hours, debris rained down on the seabed, dispersed over several square miles through the action of water currents.

TITANIC’S TOLL: SURVIVAL BY THE NUMBERS

Category

Children, First Class

Children, Second Class

Children, Third Class

Women, First Class

Women, Second Class

Women, Third Class

Women, Crew

Men, First Class

Men, Second Class

Men, Third Class

Men, Crew

TOTAL

Number Aboard

6

24

79

144

93

165

23

175

168

462

885

2223

% Saved

83%

100%

34%

97%

86%

46%

87%

33%

8%

16%

22%

32%

% Lost

17%

0%

66%

3%

14%

54%

13%

67%

92%

84%

78%

68%

Of a total of 2,223 people, only 711 survived the initial sinking, i. e. just under a third. One passenger, William F. Hoyt, died from exposure during the night in lifeboat 14 after being pulled from the water. Five others died aboard the Carpathia, leaving 706 total survivors. 1,589 passengers and crew perished. Of the first-class, 201 were saved (60%), and 123 died. Of the second-class, 118 (44%) were saved, and 167 were lost. Of the third-class, 181 were saved (25%), and 527 perished. Of the crew, 212 were saved (24%), and 679 perished (Captain Smith, as per naval tradition, went down with his ship). First-class men were four times as likely to survive as second-class men and twice as likely to survive as third-class men. Nearly every first-class woman survived, compared to 86 percent of those in second class and less than half of those in third class.

Also notable is that even third-class women were significantly more likely to survive than first-class men, with 46 percent of third-class women saved compared to 33 percent of first-class men, a result of the order to save women and children first.

Of particular note, the 35-member Engineering Staff (25 engineers, 6 electricians, two boilermakers, one plumber, and one writer/engineer’s clerk) was lost. The entire ship’s orchestra was also lost. Led by violinist Wallace Hartley, they played music on the Titanic boat deck that night to calm the passengers. There is a widespread story that they selected as their last piece “Nearer, My God, to Thee” while others say it was “Autumn.” The majority of deaths were caused by hypothermia in the 28 °F (−2 °C) water. It has been suggested that the fact that only 705 people survived when the lifeboats had a capacity of 1,178 people (54% of those onboard) could largely be attributed to the women and children first policy, where the psychological effects and resulting loss of efficiency caused the number of people saved to be only 32% of those on board. Had the lifeboats been filled, all 534 women and children could have been saved, with enough room left over for an additional 644 men.

03:00 – Lifeboat rescues

Only one lifeboat came back to the scene of the sinking to attempt to rescue survivors. Another boat, Lifeboat #4, did not return to the site but was close by and picked up eight crewmen, two of whom died aboard the Carpathia. Nearly an hour after the whole of the ship went under, after tying four lifeboats together on the open sea (a difficult task), Lifeboat #14, under the command of Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, went back looking for survivors and rescued four people, one of whom, first-class passenger William Hoyt, died later. Collapsible B floated upside-down all night and began with 30 people. By the time the Carpathia arrived the next morning, 27 remained. Included on this boat were the highest-ranking officer to survive, Charles Lightoller, wireless operator Harold Bride and the chief baker, Charles Joughin. There were some arguments in some of the other lifeboats about going back. Still, many survivors were afraid of being swamped by people trying to climb into the lifeboat or being pulled down by the anticipated suction from the sinking ship, though this turned out not to be severe. Only 10 survivors were pulled from the water into lifeboats.

This image would be on the front page of nearly every newspaper in the world at the time. A collapsible canvas lifeboat is just about to be collected by Carpathia to bring some sense of joy to a horrific event.

04:10 – Carpathia picks up the first lifeboat

Almost two and a half hours after the Titanic sank, RMS Carpathia, commanded by Captain Arthur Henry Rostron, arrived first on the scene to find the area scattered with icebergs. They started to pick up Titanic’s first lifeboat at 04:10. Over the next few hours, the remainder of the survivors were rescued. Onboard the Carpathia, a short prayer service for the rescued and a memorial for the people who lost their lives were held, and at 08:50, Carpathia left for New York, arriving on 18 April. Among the survivors were two dogs brought aboard in the hands of the first-class passengers.

On April 17, 1912, the day before survivors of the Titanic disaster reached New York; the Mackay-Bennett was sent off from Halifax, Nova Scotia to search for bodies. Onboard the Mackay-Bennett were embalming supplies, 40 embalmers, tons of ice, and 100 coffins. Although the Mackay-Bennett found 306 bodies, 116 were too badly damaged to take all the way back to shore. Attempts were made to identify each body found. Additional ships were also sent out to look for bodies. In all, 328 bodies were found, but 119 were badly damaged and thus were buried at sea.

JAMES CAMERON EXPLAINS EXACTLY HOW TITANIC SANK IN THIS VIDEO

Did poor quality steel lead to the sinking of the Titanic?

In recent times there has been much made about the fact that Titanic was constructed from inferior steel particularly brittle in cold waters.

Titanic’s steel was produced in acid-lined open-hearth furnaces, which allowed for impurities (such as sulphur and phosphorous) in the steel. These impurities led to low fracture resistance, especially in cold water conditions that reduced the steel’s ability to deform without fracturing.

However, much factual information we have discovered about metallurgy in the last century it is unfair to bring this into the equation as a crucial part of her demise.

Titanic was built from the best-known steel of the day, and there were thousands of ships built in the same era from the exact same process who never had any faults with their steel.

Titanic’s sister ship Olympic had her steel made from the exact same process using the exact same equipment, and she sailed for over another three decades before being scrapped.

Olympic even had two major collisions in her lifespan one with the battleship Hawke and another famous collision with German U-Boat U-103 in which she rammed it and sunk it. Neither of these collisions would prove particularly damaging to her hull.

So yes, Titanic would be made from better steel today, but when a 50,000-ton ship ploughs into an iceberg that dwarfs it at high speed the outcome is almost certainly going to be similar. The steel ‘myth’ is purely another small part of a very large sequence of unfortunate events.